This article is broken out from the more complete description of the

entire Turf to Tools project also available currently on this web

site, done primarily to provide an addition to the paper ‘Experiment

Archaeology & Art – the Turf to Tools Project’ currently pending

book publication.

For details on the individual iron smelts and the bloom to bar

phase, see the complete report on the Turf to Tools Project on this

web site : www.warehamforge.ca/ironsmelting/turf2tools/index.html

There is a separate photo essay illustrating the physical process of

constructing the axe from the starting blooms : www.warehamforge.ca/ironsmelting/turf2tools/bloom-bar-axe.html

Note that the numbers for images, footnotes, image credits have been

modified on this version.

Introduction : Turf to Tools

The Turf to Tools project (T2T) was undertaken primarily at the

Scottish Sculpture Workshop in Lumsden, Aberdeenshire, Scotland,

with additional work at the Wareham Forge, Ontario, Canada. The

project was initially conceived as "... an ongoing investigation in

to landscape, material and craft, inspired by local archeological

investigations in Rhynie, Aberdeenshire." (UN, 2016)

As an undertaking, T2T would be comprised of three primary working

sessions, the rough working plan was for Phase 1 (2014) to centre on

iron smelting, Phase 2 (2016) to include bloom to bar, and Phase 3

(2023) to include bar to object, with a total of eight individual

iron smelts.

Inspiration : The Rhynie Man Axe

In 1978 a large stone slab was uncovered just south of Rhynie. The

enigmatic figure carved in one surface, dubbed the Rhynie Man, would

channel the 'object' part of the project. The cartoon like figure,

likely created some time about 400 - 600 AD, holds over his shoulder

an axe. Who is depicted? What is the reason for his looming

presence? What is the original reason for the figure’s exaggerated

details : pointed teeth, big hooked nose, long hair or head-dress?

(appendix B, Rhynie as Bogie : www.warehamforge.ca/ironsmelting/turf2tools/bogie.html)

What are the construction details and use purpose of that axe? The

axe would become the goal of the extended process of ore to bloom to

bar to object. To make determining the details all the more

difficult, research suggested no artifact axes have been found in

Scotland for the period of reference. Within all of Great Britain,

only a mere handful have been found overall. Searching for a

possible artifact prototype would prove not only difficult, but the

use interpretations of that prototype became a major point of

discussion within the project.

figure 1 : The Rhynie Man picture stone, with

the axe over one shoulder.(a)

Of course extreme care must be taken with any attempt to translate

the cartoon like style of the original carving into physical

reality, most especially in the absence of any reference artifact.

At best this depiction clearly is an artistic interpretation with

proportions (and details) exaggerated for purpose, also with the

figure positioned to make best use of the shape of the natural stone

slab. The proportional size of the head of the figure is obviously

too large in comparison with the hand and body size. (Normal 'hand

width' of the human head is roughly three times the palm

measurement, in the carving this distance is closer to four.)

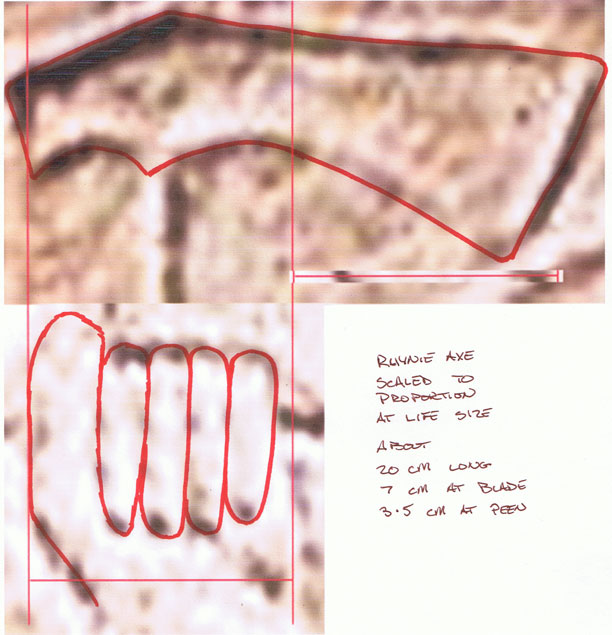

For the purposes of estimating the dimensions of the axe, the

proportion used by the original artist assumed to be accurate

between the hands and the axe. The width of the hand has been

considered at 10 cm. (1)

figure 2 : Rhynie Man Axe - converted to

'life'

This generates the rough measurements :

Length = 20 cm

Blade width = 7 cm

Peen width= 3.5 cm

Eye width= 6 cm

Of course as the image is only a side profile view. Important to

understanding the functional use and the construction methods used

in production, is also considering plan / top down view. The angle

of the cutting edge bevel determines effect on impact, distribution

of mass over the body determines handling characteristics in motion.

Obviously neither of these important defining measurements were

possible to determine from the carving.

Using the same method, the length of the handle as depicted is

estimated at roughly 80 cm. The thickness of this shaft is one

question. It is shown in the carving as a thin, single line. Is this

a reflection of an extremely small diameter, or merely an artistic

convenience? If depicting reality, this would suggest that the

object's handle would have had to have been made of iron, and at the

dimension shown, unable to structurally support the head weight, and

almost impossible to hold on to.

Searching for Artifact Sources :

" Axes, and in particular franciscas, are rare in Anglo-Saxon

graves. Some 25 axes are known from Anglo-Saxon contexts, 15 of them

franciscas. With the exception of the unique specimen from Sutton

Hoo, all English axes are early (5th-6th cent.), and all have been

found in the south (Wessex, Isle of Wight, Sussex, Kent and Essex) “

(Härke 1992) (2)

It was originally suggested that a good prototype would be the 'Axe

Hammer' from the Sutton Hoo Burial, Anglo Saxon, from southern

England, about 625 AD.

Figure 3 : The Axe Hammer from Sutton Hoo, life sized (b)

This is a unique object, without another known sample. Although

roughly contemporary, it is from a different cultural set entirely,

and also geographically distant. It also certainly appears to be a

horse-man's weapon from its overall design features.

Clear elements in the Sutton Hoo object :

• Thin forged iron handle, of a

length suitable for single hand use. The handle material shifts from

square to round profile for the last roughly 25 cm. It then ends in

a swivel mounted ring. Equipped with a leather thong loop, this is

the ideal way to secure this axe while used as weapon over the wrist

against possible dropping while mounted. Ideally the round cross

section would be wrapped with leather lace (although the artifact

did not bear traces that suggested this).

• Long drawn out peen, creating

a possible 'hammer' for dealing crushing blows.

• Handle attachment is to the

centre of mass of the total head length. This suggests providing for

a fairly symmetrical balance for a swinging impact (critical for

mounted use).

• Handle attachment eye most

likely (for functional reasons) to have been punched into the

starting bar.

• The approximate volume is 80

- 85 cc, giving an estimated total head weight of 625 - 660 gm (3)

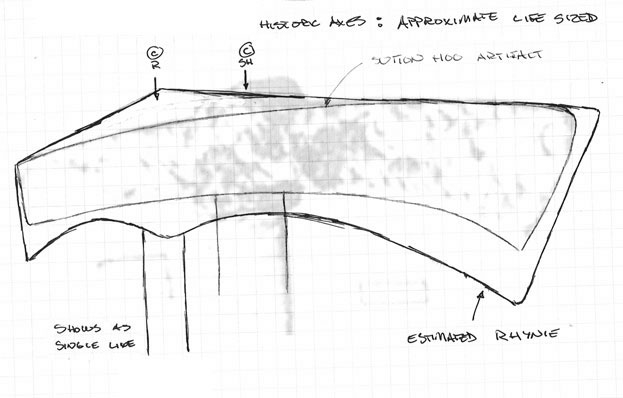

There are a number of clear differences between the Rhynie Axe as it

is depicted and the sample Axe Hammer from Sutton Hoo :

figure 4 : Profiles of Rhynie and Sutton Hoo

axes compared

• Even at casual observation,

the difference in raw size is clear between the two axes. Of course

the cross section of the Rhynie Axe can only be speculated, and this

alone will be significant in any attempt to estimate its possible

total head weight.

• Although the handle shown in

the Rhynie carving is a single line, so possibly also illustrating

an iron shaft, It is suggested here that this is merely an artistic

impression used for the ease of the original carver, and not

necessarily an accurate depiction.

• The proportion of the handle

length of Rhynie appears to be closer to 80 + cm. This handle length

is more suitable for a two handled weapon, which in fact is what is

seen in the carving. Sutton Hoo is 78 cm long, again more typical of

a two handed use, but may also be indicative of the kind of reach

needed for a cavalry weapon.

• The clear indications of

'wings' at the handle attachment point on Rhynie is a structural

feature associated with wooden handles.

• The handle attachment on

Rhynie is shown as being close to the peen end of the axe, a more

standard tool or weapon axe design. On Sutton Hoo the handle is set

roughly in the centre of the head, creating a long drawn out peen,

considered to be a secondary striking surface. At the same time,

this shape strongly influences the overall balance (and control)

while in motion.

figure 5: Replica of the Sutton Hoo Axe

Hammer

A replica of the Sutton Hoo axe was created at SSW Phase 1 as a

point of comparison, the primary difference from the artifact being

it terminated in a simple loop, rather than the more complex end

swivel of the original. Again, the replica was made from modern mild

steel, using a coal forge and large anvil. The replica was not

polished or sharpened, primarily for safety reasons while presenting

to the public. Placed in the hand, its balance and feel in motion

strongly suggested its purpose as a weapon, particularly for use

from horseback.

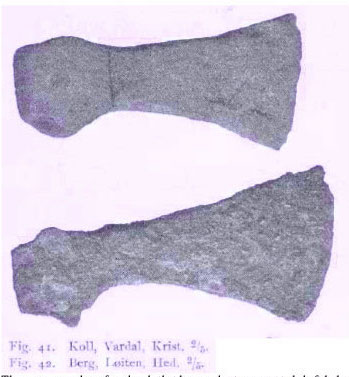

Viking Age axes (800 – 1000 AD), from Scandinavia or beyond,

although again culturally distinctive and later than the reference

time period, where deemed worth special consideration, if only for

the large number of artifact samples available.

figure 6: Type K artifacts illustrated in

Peterson's Typology (c)

Although the head shape illustrated here certainly does appear much

closer to that depicted in Rhynie, Peterson's study is of Viking Age

Norway, and the type K is described as from the 900's. (Peterson,

1919)

While observing a number of artifact and high quality replica Viking

Age axes in Denmark, there was seen a clear division between the

form of individual axes, clearly related to their primary intended

use. Those designed for combat had wide blades and were almost

triangular in overall profile, but extremely thin in cross section.

Logging axes had distinctive wedge shaped cross sections, most

commonly with fairly narrow blades. A third grouping were 'fine

tool' axes, primarily designed for wood shaping. These typically had

long double concave cross sections, making for slender (sharp!)

blades. (Markewitz, 2008)

Figure 7 : Prototype of a Peterson type K

Early in the investigations leading to T2T, a typical Peterson type

K axe had been created (at the Wareham Forge, again in mild steel,

using traditional blacksmith’s equipment), with a thin ‘fine

trimming’ edge. Set on a 60 cm long handle, it was clear to any

experienced tool user that this axe could be easily controlled to

take thin cuts off wooden beams, as for building construction or

shaping ship timbers. (Although it was also equally clear that if

used in combat it’s ease of handling would prove extremely

effective!)

In all artifact examples (regardless of origin) the body of the axes

were forged from a block of bloomery iron, either with or without an

added hard ‘steel’ cutting edge. With corrosion, the distinctive

gain lines natural to this material often indicate the exact forging

steps undertaken in forming any axe.

Again as comparison, Viking Age axes use several forging methods:

Eyes may be made by : - slitting and drifting open,

- slitting the peen end and

then wrapping to the rear and welding

- folding towards the front

and welding

Edges may be made by : - using the source iron only

- adding a lap welded steel

edge to one side

- adding an inset and welded

steel edge

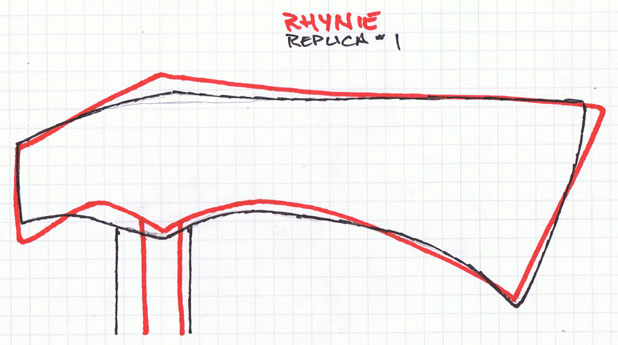

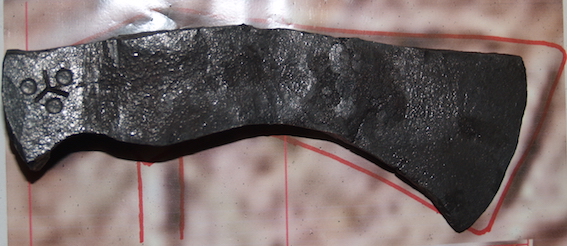

For T2T a prototype replica was made of the Rhynie Axe, taking the

discussion above into consideration.

figure 8 : Prototype of the Axe - about life sized

figure 8 : Prototype of the Axe - about life sized

Rough forged weight = 1005 gm

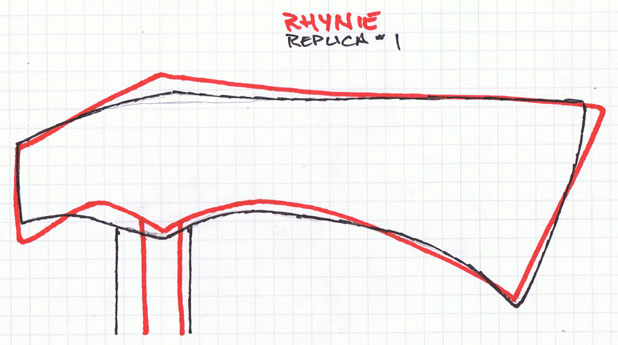

figure 9 : Comparing the replica to the carving as profiles,

life size.

figure 9 : Comparing the replica to the carving as profiles,

life size.

It can be seen that the rough forging is fairly close to the Rhynie

profile. For the replica, the eye was slit and drifted open. This

process is the easiest way to retain the quite heavy peen indicated

in the source illustration. The eye was sized to allow mounting to a

standard modern sledge hammer handle for ease of presentation (the

size used may effect the overall result). It can be seen (figure 10)

that the starting slit for the eye was made a bit too long, this

primarily a function of the available tools.

The replica was forged from a block of modern mild steel, at the

Wareham Forge, again using a ‘traditional’ bituminous coal forge and

large (225 lb) anvil. (4) The work was assisted by use of a small

industrial air hammer (which can induce certain shapes in process).

No additional hard steel edge was welded on. The finished head was

again not polished or sharpened.

The primary difference between this replica and the historic

illustration lies in the degree of the upset bottom edge of the

peen. The exact shaping around the eye wings and this peen edge

likely could have been duplicated more exactly through some final

hand forging. (After three hours of heavy work, it was decided to

stop before human error was likely!)

figure 10 : Prototype axe of mild steel - top view, life size

figure 10 : Prototype axe of mild steel - top view, life size

Without knowing the exact cross section of Rhynie, it is hard to

estimate possible head weight. If Rhynie had a simple 'wedge' form

(such as seen in Sutton Hoo) the estimated volume is roughly 160 cc,

producing a head weight in the range of 1200 + gms. This would place

Rhynie at roughly double the head weight of Sutton Hoo.

This however, is not considered the most likely cross section

however. The replica blade was shaped as a 'fine tool' cross

section. This reduces the overall weight, as a rough forging, to

1005 gm. It can be seen that the thickness of the peen is close to

that at the eye, placing much of the mass to that end of the centre

line of the handle. This overall shape results in a more balanced

distribution of weight, increasing control of the cutting edge in

actual use. The end result is a cutting tool that can be effectively

controlled (with considerable precision) even when used in a single

hand. (In contrast, axes with the simple wedge profile will 'hit

harder', but at the cost of being considerably more difficult to

control in flight.)

Although the original intent of the T2T project was to proceed from

bloom to working bar into object in Scotland, a combination of

equipment problems and available materials made this too difficult.

At the start, SSW did not have anything more than the most basic

blacksmithing equipment :

- a good sized antique anvil, but poorly mounted

- a portable ‘dish’ style forge, but in poor

repair

- no working blacksmithing hammers (although new

ones were purchased for T2T)

- a random selection of tongs, almost all too

large sized for the work involved

The huge problem turned out to be fuel. What was sold locally as

‘Smitty Nuggets’ blacksmith’s coal was the highest sulphur content

coal I ever experienced (in over 40 years of blacksmithing). Even

working out of doors, the volume of toxic smoke produced was

absolutely unacceptable. Sulphur is also a contaminant that

adversely effects forge welding ability, one of the main processes

required in compacting and purifying raw blooms into bars. Primarily

for these reasons, creation of a replica Rhynie Axe from the blooms

previously made was postponed to Phase 3, August to September 2023.

Creating the Bloomery Iron Replica :

As discussed above, the estimated weight of the Rhynie Man axe is

about 1000 gms as a rough forging. As already detailed, several

sections of the blooms created during Phase 2 where retained to be

further worked on at the Wareham Forge in Ontario. Using a simple

grinder spark test, the bloom from 2.1was found to contain virtually

no carbon, from 2.3 estimated at 0.2 – 0.3 % carbon. The combined

weight of the bloom pieces from Smelt 2.1 and 2.3 was 2042 gms, as

the starting blocks reduced to 1172 gm. These bars were further

forged to better match the pieces needed to combine into a rough

starting blank. There was additional (minor) loss, due to the

typical flaking off of hammer scale during this process. The two

plates from 2.1 were adjusted in dimension and one cut to match, the

2.3 bar cut into a small block for the peen and the other end forged

into a wide wedge for the cutting edge insert. The total weight at

preparation for the final welding up was 911 gm, with 118 gm

remaining unused.

The method chosen required two major hammer welding steps, first at

the peen end, second from the edge back towards the body, this

leaving a gap that would later be expanded to form the eye.

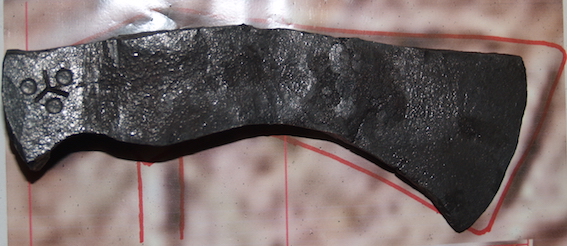

The finished replica was obviously somewhat smaller than the layout

estimate, a rough forging of 739 gm, a loss during welding and

forging to shape of a further 18% of the starting pieces. There

would be further reduction expected if the axe was polished to

‘bright’ and completed to a sharp cutting edge. (Appendix C :

Forging the Axe)

figures 11 & 12: Completed bloomery iron replica, top

and right side view (with maker’s mark), placed over

carving illustration.

In estimating the exact details of the Rhynie Man Axe, a reasonable

balance needs to be made between what is most certainly artistic

license by the original carver against a possible depiction of exact

reality. There remains the problem that there are very few existing

artifact axes to draw parallels from, and it appears none at all

from contemporary Pictish sources.

The use of the Sutton Hoo axe-hammer is suggested as not a reliable

prototype, as its design is reflected in its quite distinctive

intended function. It would appear that the primary reason for use

of this artifact source is because of the single line handle in the

Rhynie carving.

Expanding the potential artifact examples to include roughly

contemporary Viking Age axes, of which there are certainly a great

number, is strongly suggested here. The best 'fit' appears to be the

Peterson Type K axe (admittedly, Norwegian and some 200 years

later), plus numerous examples seen in Denmark. Combining these

examples with actual forging methods, with a consideration of

experience in actually handling axes of various types, does suggest

this a 'most likely' prototype design.

The Rhynie Man Axe is thus considered a 'fine tool' type, roughly

1000 gm in head weight. It may have had either a slit and drifted

eye, or an eye formed by slitting and welding the peen end, possibly

a peen enlarged by welding in an additional block. It is not

possible to tell if the blade would have had an inset carbon steel

edge, but this is likely considering 'best possible' tool making

practice. The high status attributed to the Rhynie Man certainly

would demand this quality. Of course the actual angle of the cutting

edge best determines potential use, and this remains quite unknown

from the reference carving. Such a head, fitted with a wooden handle

in the 60 - 80 cm long range, would produce an object easy enough to

control with a single hand, but also producing considerable power if

swung with two. It easily could have been a dual purpose tool or

weapon, able to create fine shaping cuts in wood - or devastating

power in battle.

Although the intent of Phase 2 was to devote several working days to

the second stage process, bloom to bar, followed by the third stage,

bar to object, this in the end did not prove possible. After several

quite unsatisfactory tests, and considerable outside consultation,

it was found that the 'best' available coal was in fact imported

from Poland. This itself was a major surprise, and certainly

reflects directly back to the framing concept of human impact on

natural resources, a process certainly much more dramatic in our

current age.

figure 13 : Posing as the Rhynie Man in 2014 (d)

figure 13 : Posing as the Rhynie Man in 2014 (d)

The axe used here is the Early Viking Age replica discussed

above.

The handle length is 66 cm.

Image Credits :

Note : In preparing this report, much use was made of modifying

images via Photoshop to alter scale and proportion. Available

images were re-sized to life to allow for more consistent

measurements and to serve as a close comparison during the making

process. Apologies are given for the poor quality resulting from

this method. Certainly considerable care must be taken with this

kind of data generation method. (Obviously first hand examination

of actual artifacts would be ideal, but in this case was not

physically possible.)

a) Unknown / Visit Aberdeenshire, (date?), ‘The Rhynie Man,

Aberdeenshire Scotland’, (web page), used without permission :

https://www.visitabdn.com/listing/the-rhynie-man

b) Angela Care Evens (?) 1986, ‘The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial’,

pg 42 (modified), used without permission

(A portion of the original excavation report, by Rupert

Bruce-Mitford, was also available as a reference here.)

c) Petersen, J., 1919, ‘De Norske Vikingesverd’, via internet

source (direct download of portion of document scanned as pdf), used

without permission

d) Kelly Probyn-Smith, 2014, used with permission

Footnotes :

1) A traditional measurement, ‘one hand’ (commonly used to measure

the shoulder height of horses) was considered to be 4 inches = 10

cm.

2) “ The francisca (or francesca) was a throwing axe used as a

weapon during the Early Middle Ages by the Franks, among whom it was

a characteristic national weapon at the time of the Merovingians

(about 500 to 750 AD). It is known to have been used during the

reign of Charlemagne (768–814). Although generally associated with

the Franks, it was also used by other Germanic peoples of the

period, including the Anglo-Saxons; several examples have been found

in England ” (Wikipedia, ND)

3) Initial estimates were generated by making modelling clay

replicas, then determining the volume and multiplying by density.

Historic wrought iron will be somewhat less dense than pure iron (at

7.87 gm/cc), so a multiple of 7.8 gm/cc has been used. ( Data from

‘The Material Property Database’ : www.matweb.com

)

4) It is worth remembering that the ancient blacksmiths who made the

artifacts would have been working on small iron anvils, generally in

the range 10 cm on a side (from a single bloom) or even flat block

of stone. Forges would have been ground mounted and fired charcoal,

which would be more difficult to generate high welding temperatures

over large objects like axe heads.

References :

Evens, A. C., 1989, ‘The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial’, British

Museum Publications, London UK

Härke, H., 2010, ‘Weapons: axe, swords, spears, shields. The

weapon burial rite at Blacknall Field’, in ‘The Anglo-Saxon

cemetery of Blacknall Field, Pewsey, Wiltshire'

(Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Monograph No.

4), Annable, F.K. & Eagles, B. N., pg 7-17, (internet

sohttp://forum.blankvaapen.org/showthread.php?t=744urce) last

accessed 7/24/23 : www.academia.edu/1178534/

Markewitz, D., 2008, 'Exploring the Viking Age in Denmark', CD-ROM,

The Wareham Forge, Canada

Petersen, J., 1919, ‘De Norske Vikingesverd’ via internet

source (direct download of portion of document scanned as pdf) : http://forum.blankvaapen.org/showthread.php?t=744

Wikipedia (unknown), ND, ‘Francisca’ (web site) last accessed

7/24/23 : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisca

(unknown), 2016, ‘From Turf to Tools’ , in SSW News (blog

post) last accessed 7/20/23 : https://scottishsculptureworkshop.wordpress.com/projects/from-turf-to-tools/