Note: I get a number of requests each week via e-mail about various objects from the Viking Age. A good number relate to knives. To avoid me repeating myself, I have put together this piece, which may prove the starting point for a more comprehensive survey in the future...

In preparing this essay I have relied heavily on :

'Anglo-Scandinavian Ironwork from Coppergate' by Patrick Ottaway (York Archaeological Trust, 1992)

Many observations were drawn from my own personal studies of the material culture

of the Viking Age, plus work I have done on a number of major museum exhibits.

Add to this over 25 years practical experience as a blacksmith specializing

in historic forms and techniques.

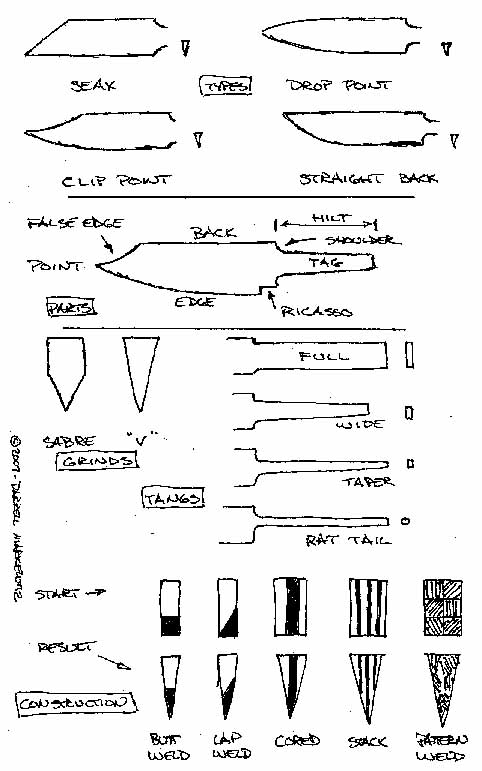

There appears to be no standard nomenclature for describing all the various features related to knives. The illustrations below will diagram the terms that I will be using relating to blade profiles and construction methods.

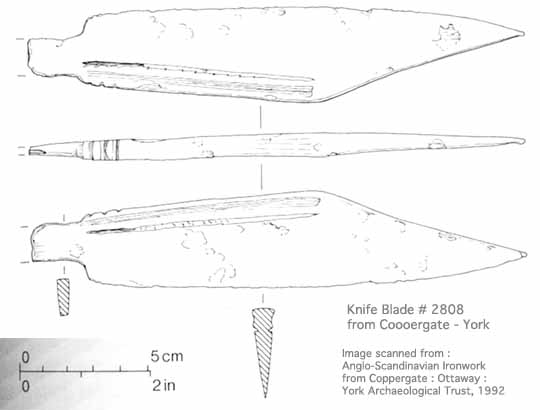

The term 'pattern welding' is used here in its archaeological definition (rather than as the term is incorrectly used by many contemporary knife makers). The method appears to have been invented in Europe some time around 100 - 200 AD. The first blades showing the technique are often found in a Roman military context. At its simplest form, pattern welded blades start as a pile of stacked plates of iron metals of varying carbon content. It is common to see starting stacks of 7 or 9 layers, this number not due to any mystical purpose. The simple reason is that the physical size of the stack lends itself to effective heating and hammering. The plates are secured together and forge welded into a solid block. This block is then drawn to a long rod and twisted. Several such rods are then welded together to form the body of the billet from which the blade is forged. By alternating direction of the twists, or twisted and straight sections, highly decorative patterns can be produced. The set of V shaped lines generating a herring bone effect is most distinctive of the technique. Some detailed artifact drawings from York show come of these construction details.

The problem that the serious re-enactor has when considering the knives used during the Viking Age often comes down to a simple one of lack source material. In most popular overviews of Norse physical culture, knives may be at best covered by a few lines and perhaps an image or two of an artifact. Even in the more academic publications, there are few that deal with iron objects in detail, much less knives specifically. (An exception would be 'Knives and Scabbards' from the excellent 'Medieval Finds from Excavations in London' series. Unfortunately, the earliest blade detailed in that volume is from the early 1100's.) Generally, most archaeological sites are unlikely to yield more than a handful of knives, so finding detailed descriptions means digging through a large pile of often hard to access reports. One exception to this are large scale excavations of Viking Age town sites which have been undertaken in the last several decades. The Coppergate site at York, England has yielded over 200 knives, Helgo at Sweden a similar number, and Woods Quay at Dublin Ireland is reported to have produced over 400. This report is primarily based on the Coopergate materials, as I have not been able to acquire a detailed report for the Helgo excavations, and the Woods Quay materials are sadly yet to be published.

Looking over grave finds from across the Norse world during the Viking Age,

one fact does become obvious. Knives were considered essential tools, and appear

to be carried by everyone. There is no limitation on this use, either by sex

or age. This also seems to apply to the entire spread of both time and geography.

There is a slight tendency for the heavier seax style blade to be found in male

burials, most especially when it comes to the longer combat variations. This

is not a clear cut division however, and may have somewhat to do with the flexibility

in women's roles in Norse society.

Most knives in the Viking Age will taper in thickness slightly as they run from

the hilt to the point. This feature is most likely a result of the smith wanting

to stretch the metal to get as much length as possible. It also tends to effect

the handling of the finished knife. The greatest weight of the blade is placed

closest to the handle, making the tip feel light and increasing control. This

does tend to reduce the relative impact force that can be delivered towards

the working end of the blade. Generally there is little hard data recorded (even

in primary reports) on the degree of taper on any individual object, other than

noting the shape in general.

The first overall consideration when looking at knives from the Viking Age is

shape and size. Generally we can break the blade shapes into two main groups,

the classic 'small tool' and the distinctive 'seax'.

The small tool blade shape is one of the most ancient. It can

trace its development back at least to the first use of copper (copper) cutting

edges, perhaps even back to the neolithic period. At its simplest, the small

tool is a long thin triangle with one edge sharpened. The point may lift above

or drop below the mid line of the blade. Generally both the back and edge will

be relatively straight, with some amount of curvature to either surface towards

the point. Generally the blade is considerably long in proportion to its width.

In the collection from Coppergate, knives of this profile make up 55% (98) of

the total number.

The 'seax' is a specialized variation of the more generic 'clip point' style.

In the seax, the edge is basically straight. The back will make a dramatic diagonal

slope down from its widest point towards this edge to create the point. The

word 'Seax' means 'knife' in the tongue of the tribe who came to be known for

their distinctive knives - the Saxons. The seax shape has a number of variations,

but also was a popular blade shape for the Norse. The profile creates a sturdier

and heavier blade, well suited to tasks like splitting kindling.

There are three basic modifications to the overall layout:

- The back and edge can be roughly parallel to each other.

- The back can lift upwards slightly from the tang towards the start of the

diagonal.

- The back can taper down slightly from the tang towards the start of the diagonal

cut. (This form uncommon in the historic period)

Seax blades from the Viking Age almost always have either parallel sides or

taper upwards to the cut. In some cases the diagonal cut is a shallow concave

arc. One reason to produce a blade with its greatest width just at the start

of the downwards cut is to increase the impact energy delivered by a downwards

hacking stroke. This feature is most desired in heavy tool or certain styles

of combat knives.

When taking a look across the entire collection of 200 plus knives

found at Coppergate, The first thing that strikes you is the relatively small

size of the individual blades. Of course certain care must be taken before applying

measurements from this sample to the wider Norse Culture. Perhaps most importantly,

the objects found at Coppergate can be considered to represent 'lost' items.

It is unlikely any of these items were intentionally deposited, as is the case

with blades found in graves for example. Smaller items are certainly more likely

to be lost than larger ones, both due to size alone and the effort likely to

be expended in finding bigger, and thus more valuable, pieces. Despite this,

the fact that there is such a large number of objects found certainly suggests

they existed commonly enough that many could have been available to be misplaced.

'Anglo-Scandinavian Ironwork' charts out the individual knives in graphs that

describe a number of physical characteristics. There are definite spikes when

grouping the found knives by blade length and width:

In terms of blade length, there is a clear preference for blades between 60

- 70 mm ( 2 3/8 to 2 3/4"). The majority of the samples fall in a range

between 50 - 80 mm (2 to 3 1/4")

In terms of blade width, there is a clear preference for blades between 12 -

13 mm (roughly 1/2"). The majority of the samples fall in a range between

10 to 16 mm ( roughly 3/8 to 3/4")

It should be noted however that of the 211 knives described, only 34 are some

variation on the seax pattern. From the objects depicted in the scale drawings,

it would appear that these seax blades primarily form the majority of the larger

blades in the collection. Two are roughly 140 cm (5 3/4") and one at 20

cm (8") blade length. The width of these particular blades is roughly +

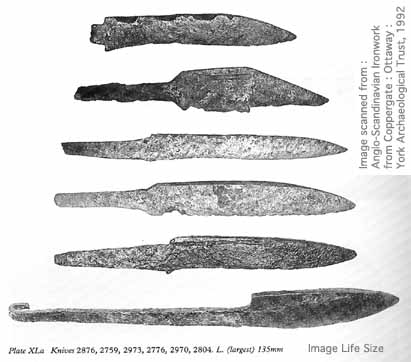

25 mm (over 1"). It should be noted that Ottaway states in the text : "Knives

as long as 2756, 2799 and 2808 are unusual..."

A table style comparison of was prepared listing details of 28 of the knives

found at 16 - 22 Coppergate. To prepare the table, measurements were taken from

the scaled drawings, descriptions and other date presented in 'Anglo Scandinavian

Ironwork from Coppergate'.

Because of the number of variables plotted, this large table can be seen as

a separate sheet HERE.

Samples were chosen to represent the primary types found. Total length is given

for only those knives that retained their full tangs. Although a number of blades

were sampled for metallographical analysis, in most cases these tended to be

the more fragmentary objects. For that reason construction details were only

available for less than half the objects selected for the table. Some care has

to be taken when applying measurements from the artifacts to modern reconstructions,

as almost all the blades found at Coppergate show considerable wear - the results

of full and useful lives.

Regardless of the actual profile of the blade, Most knives in the Viking Age

have a fairly pronounced V shaped cross sections. They tend to be fairly robust

in the maximum thickness at the back of the blade as well, especially when considered

in terms of the width of the blades as discussed above.

There is considerable variation on the material that composes the blades themselves.

As might be expected there is a wide range of both raw materials and techniques

represented. Many of the samples at Coppergate appear to have had a harder higher

carbon 'steel' applied for the cutting edges and softer low carbon iron for

the backs, at least originally. (Those blades with extensive wear often showed

little or none of the steel layer remaining as the result of endless sharpening)

The collection shows a range of methods of welding together these different

materials, ranging from simple butt welding, inset edge, through layered stacks

to five knives that show distinctive pattern welding. Generally some kind of

butt welded or inset harder steel cutting edge on to a soft iron body is the

most commonly seen construction method.

Viking Age knives almost always have narrow tangs - often narrower than would

be considered standard for a modern bladesmith. Generally these are rectangular

in cross section, and almost always have a considerably narrow width compared

to that of the blade. They also will taper sharply along their length towards

the tip, generally extending the entire length of the handle. The shoulders

between tang and blade are generally rounded, indicating they were forged into

shape. Rarely do tangs show any holes indicating rivets were used. In those

knives with complete tangs remaining, the ends of the tangs are either folded

over or mushed indicating peening.

Handles when found are almost always solid tubes, or in some cases a series

of barrel shapes. The standard method of attaching the handle was to drill or

burn a hole down the centre of a block of wood, antler or bone and insert the

tang through this hole. The blade end of the hilt material would be carved out

to accept the shoulders, so the handle would fit up snug to the full width of

the blade. In some cases a metal disk was then used to cap the handle material

(much like a washer). Regardless of the use of a top cap, the end of the tang

was then hammered to spread it, thus holding the handle in place.

Handles are often found carved, with a range of skill exhibited by the artisan

who undertook the work. This may range from simple inscribed lines to full relief

carvings of knotwork or animals. The handle material may also be reinforced

by the use of wrapped wire or metal bands formed from soldered sheet.

Knives almost without exception do not possess any kind of guards. The first

reason for this is a purely technical one, based on the construction method

discussed above. The rounded shoulders most typical of all Norse knives would

make fitting any kind of guard tightly extremely difficult.

Scabbards are most commonly of the pouch variety, which again is a reflection

of the construction techniques used. These pouches usually cover almost all

the hilt, so that only a small amount of the handle material protrudes from

the leather case. This makes for a very secure holding method, but does mean

that drawing the blade is fairly difficult. Knives most often hang from an upper

loop or slot and so at right angles to the belt. In graves these are often found

positioned on the left side of the body. In some cases smaller knives are found

in woman's graves such that they must have hung from the broaches or been attached

to the bead festoon. (The size of the blade and the location both suggest use

as textile tools.)

Some pouch scabbards are reinforced with a metal strip down one side. Most commonly

any metal mounts on scabbards are made from bronze. Scabbards for larger knives

will often have two support loops through this strip. These are commonly found

positioned on the skeleton laid flat across the stomach, handing with the hilt

to the right.

Iron knife with silver wire in the area between the handle and

the blade.

From a female grave (grave 503 at Ihre, Hellvi parish, Gotland). 9-10th C.

Viking Age knife from Gotland. Reconstructed by Craig Sitch.

Both illustrations above from 'Viking Knives from the island of Gotland

Sweden' by Dan Carlsson (ArkeoDock, 2003)

Everything about the physical structure of the majority of knives from the Viking Age indicates a perception of knife as tool - not knife as weapon. The primary reason to equip an knife with a guard is to protect the hand during fighting. As the artifacts prove, the standard Norse knife is not equipped with a guard. The most common pouch scabbard is designed to be protective and secure - but the style makes it extremely difficult to draw the blade with any speed. The majority of samples are also small, a size that well suits a working tool rather than a combat weapon.

The images shown have been scanned from the texts credited. Note that these images are being used without permission. I strongly recommend that anyone wanting a fuller understanding of this topic simply PURCHASE the volumes indicated.

'Viking Knives from the island of Gotland Sweden' by Dan Carlsson (ArkeoDock, 2003)

Anglo-Scandinavian Ironwork from Coppergate by Patrick Ottaway (York Archaeological Trust, 1992)